There Is Nothing a Needle Cannot Fix

On rainy village days beneath tiled eaves, women stitched quietly as the sky wept, weaving warmth and memory into every seam. Decades later, across an ocean and a lifetime, the thread finds its way back into the author’s hands. In this lyrical meditation on mending, identity, and the beauty of slow creation, she rediscovers the art of handcraft—not just as a skill, but as a way of healing, remembering, and becoming whole again.

CULTUREUPCYCLEENGLISH

Sophie Liu-Othmer

6/3/20256 min read

When I was a child, my family lived in a village called Nan Song (南宋) in northern China, specifically in Chang Zhi, Shan Xi Province. One vivid memory from my childhood is of women sewing on rainy days when they could not work in the fields or venture down the hill to gather plants for the pigs.

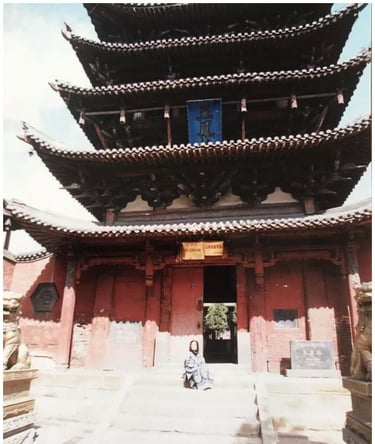

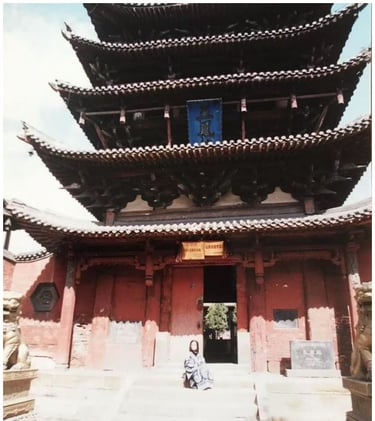

The famous “Five Phoenix Temple” 1271-1368 AD in Nan Song

They gathered on straw mats outside our adobe house, sheltered beneath the tiled eaves. Their hands were busy mending clothes or finishing new garments and shoes for their families, preparing for the upcoming Chinese New Year.

Though these hours may have seemed dull, they stuck in my mind for that very reason. As a child, I was confined indoors by the rain and found myself sitting with these women—not my own mother, who was from the city and unfamiliar with needlework.

I often sat beside a grandmother in our living quarters on rainy or snowy days, captivated by her craft. She skillfully used a spindle to make thread and a hand drill to create shoe soles.

Author wears a pair of handmade winter shoes.

To make those soles, she carefully cut out pieces from a pattern, cooked glue, layered the soles with old scraps, and meticulously glued, drilled, and stitched them together, one stitch at a time. Hours slipped by unnoticed; we exchanged few words, but I was mesmerized—so much so that I forgot I needed to use the bathroom. One particularly frigid winter day, when I finally rushed to the outhouse, I struggled to unbutton my cotton-padded overalls due to frostbitten fingers and ended up wetting my pants. It was a disaster—and just one of many stories to tell.

Every winter we get frost bites on our hands and feet.

People made their own clothes and shoes out of necessity; we were poor and could not afford to buy anything. Moreover, there were few stores that offered machine-made goods. This was simply how people had lived for centuries in China.

It was common to see people wearing mended clothing. Crafting a new item could take a woman an entire season, as there were limited hours in the year for sewing amidst farming duties. After China adopted textile manufacturing and sewing machines, handmade items slowly faded from everyday life, often viewed as relics of a bygone era—shameful symbols of poverty and backwardness.

I left China in 1987 for America, which I believed to be the land of unparalleled wealth, technology, and opportunity. I convinced myself that I should be able to own anything I desired. Initially, I arrived without a dime. Gradually, I accumulated more wealth—a series of cars, houses, clothes—upgrading from $10 shoes to $600 pairs. I amassed over 100 pairs and constantly browsed online for my next purchase.

Now, at 60 years old and having lived in America for 38 years, I grappled with a different reality. As an extrovert, the shift to working from home during COVID was particularly challenging. The very air—essential for life—became threatening. I developed cabin fever, dubbing my suburban home a “cemetery for living people.”

In response, I began to take more walks and immerse myself in mushroom foraging, carrying a wicker basket and wandering through the woods for hours—it became a part of my new lifestyle.

In the winter, I rekindled my love for needlework, embracing mending, sewing, and felting solely by hand. Although I own a sewing machine, I find greater joy working with my hands. Now, as an introvert, I prefer staying home and not talking. Talking to people makes me tired. Driving to places wastes a lot of time, and in the meantime, I have so many fun projects to do and so many forests to explore.

Indeed, America is a land of freedom and opportunity. Yet, among the invaluable lessons I’ve embraced from Western culture is the freedom and the opportunity to affirm the Chinese aspect of my American life. Discovering what it means to be Chinese through living in America—this may sound ironic—yet it is precisely this realization that has become the most significant insight I’ve gained in America and Western culture.

I am a Chinese American. I long for the sewing and mending of my childhood on rainy days, the company of village women, their weathered hands, the wrinkles on my grandmother’s face, and the joyful mingling of their laughter with the sound of raindrops.

Each day, I eagerly sit down to craft with my hands. It is thrilling, relaxing, and fulfilling—a chance to weave a piece of my history and experiences from China into my work and give them a newfound appreciation. This creative expression has transformed me into an artist.

Moral hunting May 2025

His words encapsulated my teaching experience—reminding me how precious focus and perseverance are, serving as the secret ingredients to success in life.

The value of needlework is indeed universal. During a visit to my Italian friend Marco in Milan, he asked me to wait for him near a sculpture called “Needle,Thread and Knot” that symbolizes the city's fashion legacy.

Value is relative. What holds significance for a small group in a village may be perceived differently by a larger community. My individual relationship with needlework, rooted in Chinese tradition, contributes to a collective appreciation shared across the globe.

Needle, Thread and Knot, Photo source from Wikipedia

Needlework and Stitching Workshop at the ZIRAN Fix-it Clinic - Asian Fair, May 2025

Living in America has allowed me to reflect on my Chinese traditions from a new vantage point, enabling me to compare them with the diverse customs of others worldwide.

Like the act of upcycling, a broken heart not only heals but emerges stronger, embodying a newfound beauty. Just as mending a piece of clothing, we not only fix it, but also use the hole as an opportunity to maybe patch an embroidery of a beloved animal while reinforcing the surrounding worn-out area with stitches of sunshine on a hill.

Chinese handcraft entering the world of high fashion.

Author and her friend Lisa Niu showcasing upcycled antique dragon motifs in haute couture at the Asian Fair 2025.

Author bio:

Sophie Liu-Othmer is a teacher, writer, and fabric artist currently working as a senior Database Administrator in a bank. She is deeply involved in her community, believing that family and community are vital to a thriving society, and has many years of experience teaching World History and Chinese. In her free time, she enjoys sewing, mushroom hunting, gardening, cooking, and traveling.

Recently, at an Asian fair, I was invited to teach people how to make mugwort pouches, which can be hung on backpacks, belts, or in cars, bringing a touch of nature and healing. In a session for children aged 7 to 12, I began by asking if they had at least half an hour to dedicate. If not, they should reconsider joining. "If you want something quick, this project isn't for you,” I explained. They all nodded, accompanied by their parents.

From the initial hesitation of handling needles to mastering basic stitching, the young learners impressed me. One boy, a newcomer to needlework, successfully completed a line of running stitches—exactly what I hoped to see. He used that same stitch to close his pouch and then asked, “Can I make another one?” Due to limited materials, he had to wait—but when he was given the green light again, he dove into it with enthusiasm. Hours slipped away; his father remarked, “I’ve never seen him so focused,” and “He has never sat still for this long.”